Our Assessment Framework

Our Assessment Process

Assessing the current capacities of a movement system that is extremely complex is a challenging process. This is why we must have a framework to guide our assessment process.

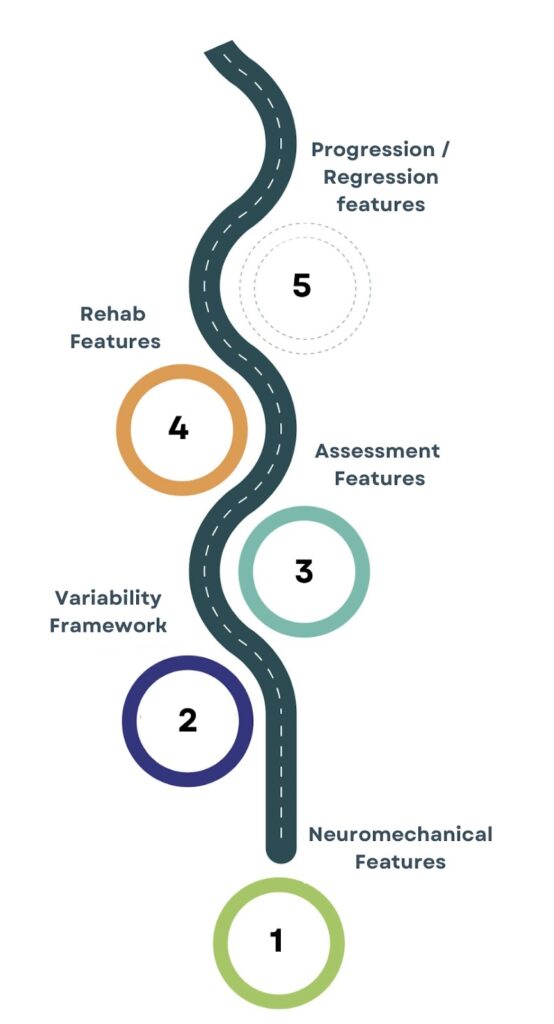

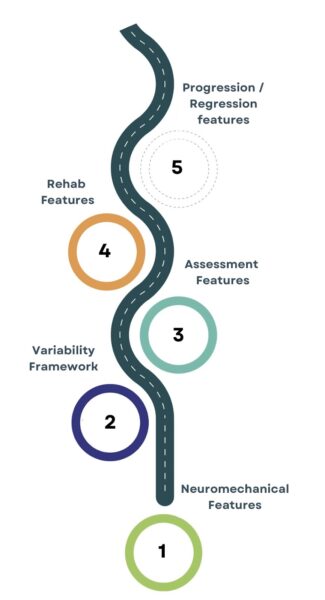

In part 1, we described some of the key neuromechanical features that are based on the architectural design of our anatomy,and how we use those to guide our thought process.

In part 2, we explored the importance of using a movement variability perspective to organize our thought process, instead of trying to identify “faulty” or “dysfunctional” movement.

In part 3, we will explore how we can integrate that information into a more structured assessment framework to guide how you will approach the early phases of treatment & rehab.

Gathering Information

People typically come to see healthcare professionals with a problem that they want you to solve, and in order to work with them to find a solution, we need to understand their situation from a subjective & objective perspective.

The subjective assessment is all about gathering information from our patient/client about their main problems/concerns, and we must give them time to share their story and explain their situation in their own words.

Below we will outline some key components of our subjective examination and explore how this information can help guide our objective assessment.

Individual perspective

- Give them time to share their story in their own words so that you can appreciate how this problem is influencing their life.

- Is their problem related to pain, or do they share more about how that pain is impacting their function and how they are struggling to engage in meaningful activities?

- If their concern appears to be more related to function, then we need to ensure that we are using these functional goals to describe the intention behind our treatment/rehab strategies, i.e., they probably won’t care about the importance of changing muscle & joint/segmental variability, but how that variability relates to their ability to engage in those meaningful activities.

Pain features/symptom behavior

- What aggravates & eases their pain and how might this guide what we may need to assess further during the objective assessment.

- E.g., a client who only experiences low back pain after a long walk vs a client with low back pain who feels better after a walk may need different capacities during rehab.

- If their low back is more sensitive after a long walk, we would be suspicious of the capacity of the lower limb to be able to manage & distribute the forces acting on the lower limb. If the lower limb can’t manage those forces, might this change the behavior and/or sensitivity of the lumbar tissues?

- If my low back is more sensitive after sitting for long periods of time, but feels better after a walk, then yes – we may simply need to move more and expose the lower limb tissues to more force. But, we would also be more interested in the local variability of the muscles & joint / segments around the lumbar spine vs the load capacity of the lower limb.

Past injuries/pain experiences

- How might these influence how stress & load is being distributed across your movement system?

- E.g., consider a client with a current experience of anterior knee pain, who has been working on quadricep & hip strength, but is struggling to improve after 3 months of rehab. However, their therapist never dug into their past injury history which would have revealed numerous lateral ankle sprains on the same side. Might there be a lack of capacity through the foot & ankle that may perhaps be leading to an overloading of the knee structures? It’s worth exploring this further in the objective assessment!

Past treatment strategies

- What has helped or hasn’t helped them in the past and how can we use this to guide a clearer plan ahead?

- E.g., consider a client with persistent low back pain who has been working on trying to “correctly” stabilize their core muscles during movement tasks, but has not noticed improvements. Does this mean they weren’t “correctly” stabilizing their core, and that we need to show them a better way!? Or does it simply mean that this strategy is probably not what their body needs to restore variability. We need to dig deeper during the objective assessment to paint a clearer picture.

Psychosocial considerations

- How might non-physical stressors (beliefs, fears, anxiety) influence the clients movement variability?

- Personal experience: I had a client recently with low back pain who sat & stood with a very extended spinal posture. They felt better when they slouched (spinal flexion), and worse when they extended, but they continued to extend because their doctor told them that flexion was dangerous!

- So, even though they felt better in flexion, they still continued to hold themselves in the painful posture based on an inaccurate belief about spinal flexion!! From a rehab perspective, we needed to reframe this belief before progressing with loading strategies to help restore variability.

This is not an exhaustive list, but they do represent some of the key features that help us generate a clearer picture of the individuals main concerns, and how we can organize our objective assessment to identify their current movement capacities

Objective Assessment

The objective assessment deals more with the process of identifying the current movement capacities of the individual, and this is where appreciating the information covered in Part 1 & Part 2 becomes important. Below are some important features.

Limb vs Midline Behaviour

From a neuromechanical perspective, the limbs take on a different role to the midline when it comes to managing the external forces acting on our system, mainly because they are in direct contact with those forces (the midline rarely dealing with direct forces outside of some sports or prolonged positions)

A limb (upper & lower) that can handle forces well often affords a midline / spinal region more variability (greater movement options). This is why when someone lacks variability at the neck, thoracic spine / rib cage, or low back, it’s very important to assess these local areas within the context of the associated limb.

Considering the different roles of the limbs & midline, we carry out our assessment process in a proximal to distal manner, regardless of where the client’s current complaint is. This proximal to distal assessment helps us understand the behaviour of proximal & distal regions within the context of the local areas experiencing pain and/or movement limitations.

Again, this is just one of many neuromechanical features that guides our assessment, but it’s an important one.

What are we assessing?

First & foremost, we need to rule out red flags or signs of structural pathology.

Then, we’re assessing the current capacities of the client within the context of their unique problem/concerns. We are not looking for “dysfunctions” or “faulty” movement, but simply assessing what the individual is currently capable of / not capable of.

Local muscular variability

- Can muscular tissues lengthen & shorten to afford space for the segments to move?

- Can muscular tissues manage forces with variable contractile behaviours (isometric, concentric, eccentric)

Local joint / segmental variability

- Can the relevant joints demonstrate full physiological range of motion?

- Can the relevant segments move relative to each other, i.e., express dissociation?

Global coordinative capacities (intermuscular & interjoint variability)

- Can the relevant muscles share & distribute forces well between them?

- Can the relevant segments coordinate with each other to distribute motion?

Sensitivity (are those movements painful / uncomfortable / sensitive?)

- Don’t characterize sensitive movements as problematic, but try to consider why they might be sensitive.

- Is there sensitivity because there’s a fear that the movement may be damaging, which increases the sensitivity in the nociceptors?

- Is the movement sensitive because the local muscles & joints lack the capacity to share stress/load?

- Is the area sensitive because it’s being overloaded with force management/production responsibility, because another area isn’t contributing?

- Is the area/movement sensitive because that area lacks the capacity to share/coordinate muscular & joint load across a broader area / with other neighboring tissues?

- Is the area sensitive because they are maintaining protective behaviors from an older/acute injury? Once protective, now provocative?

There are lots of potential reasons that movement can be painful / sensitive, but instead of avoiding them or calling them “faulty,” we need to try to understand what the potential drivers of that sensitivity are.

Our Assessment Framework

This hopefully helps to provide you with a clearer insight into our assessment of our framework, and how we use it to establish an entry point to rehabilitation / loading.

We need to conduct a solid subjective assessment to understand the unique factors that are connected to the individuals main problems / concerns, and we also need to organize our objective assessment in a manner that allows us to appreciate the current capacities (level of variability) that their system has access to.If you made it this far, thanks so much for reading, and we’ll chat again in Part 4 – our rehabilitation framework!